By Jay Weiner, The Washington Post

It is Wednesday, Nov. 3, in the wee hours of the morning after election night.

From Chicago to Las Vegas, from West Virginia to Colorado, exhausted campaign managers are on their BlackBerrys and iPhones, talking, e-mailing and texting with election lawyers and party operatives in Democratic and Republican bunkers in Washington.

The word on everyone’s lips? “Recount.”

As the sun rises, final returns will begin to trickle in from the most remote precincts and the most disorganized counties. Problems with provisional ballots will emerge in some states. Issues with absentee ballots will develop in others. Disputes will crop up; battle lines will be drawn. And a recount — or two or three — will arise somewhere, throwing the results of the 2010 midterms into doubt and leaving the fate of the House, or more likely the Senate, up in the air.

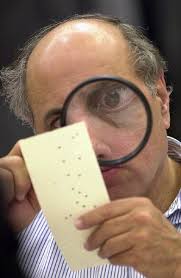

We all remember 2000. But it also happened in 2008, when the recount in Minnesota’s Senate race between Democratic challenger Al Franken and Republican incumbent Norm Coleman helped nail down the 60th and (if only for a brief time) filibuster-busting seat for the Democrats. The process took eight months and showed that Franken won by 312 votes out of nearly 3 million cast. Six months after he was sworn in, Franken voted for national health-care reform. The recount affected policy and changed history.

Now, with less than three weeks until Election Day, polls show that at least a half-dozen Senate races are too close to call, and perhaps four or five times as many House contests are undecided. Of course, not all of these races will end in uncertainty, but on Nov. 3, the country could wake up and find it has several recounts on its hands.

With so much at stake this year, and with the lessons and emotions of Minnesota 2008 and Florida 2000 lingering, recounts will almost certainly trigger an all-out assault from Washington-based election stars such as Marc Elias, who oversaw Franken’s legal team; Ben Ginsberg, who was instrumental in helping George W. Bush beat Al Gore; and Chris Sautter, the Democratic recount guru who has been involved in just about every major recount since 1984. The parties are already mobilizing their volunteers and lawyers.

Election laws and standards vary from state to state, so no recount is the same. (Bush v. Gore was about shutting down the Florida recount, for instance, while Franken v. Coleman was about looking under every rock for more votes.) Fraud and shenanigans are rare. The results don’t get twisted; they get verified.

But they get verified differently. Some states have mandatory recounts, triggered by margins of less than, say, one-half of 1 percent. Others, such as Nevada, which could be a recount hot spot next month, simply allow the trailing candidate to call for a recount if he or she thinks victory is at hand and is willing to pay for it. The odds are not great; flipping an election result via a recount is unusual, hinging on how many mistakes election officials made or how many previously uncounted or miscounted votes the losing candidate can pick up. And in a midterm election, with lower turnout than in presidential election years, mistakes are likely to be fewer.

Still, if a candidate really wants to “pull an Al Franken” — as tea party challenger Joe Miller suggested Sen. Lisa Murkowski might be doing when she hired a lawyer to prepare for a possible recount in Alaska’s Republican primary in August — or, for that matter, “pull a Bush” (minus the help of the Supreme Court), there is much to be learned from those 2000 and 2008 recount battles.

A few of the key lessons:

— If you’re a candidate who hasn’t hired a recount lawyer yet, you’re probably too late. In 2008, Franken’s campaign had a local lawyer working on detailed recount plans a month before the election, way before Coleman’s side. You also need to prepare early for a potential trial, or at least a series of recount-related legal hearings. In 2008, Franken’s lead trial lawyer was on site in November prepping for courtroom action; Coleman didn’t hire his lead trial lawyer until days before proceedings began in January. Guess who won the trial.

— Set some campaign funds aside to cover costs. Few recounts are likely to cost the $20 million that, according to my calculations, Coleman and Franken combined to spend during their saga, but generally they cost a bundle. In 2000, the Gore and Bush camps spent a total of $17 million during their 36-day recount. Washington lawyers don’t come cheap.

To read more, visit: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/10/15/AR2010101502804.html?sub=AR